Become NORWEGIAN

SPEAK AND THINK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

AUTHENTIC NORWEGIAN LIVING

From the Viking Age in the late 8th and 9th centuries to its unification under Harald Fairhair, Norway has shaped the cultural and historical landscape of Northern Europe. Its heritage reflects a blend of Old Norse traditions, medieval kingdoms, seafaring exploration, and later centuries under Danish and Swedish rule. With its dramatic landscapes, stave churches, and preserved coastal towns, Norway offers a timeless journey through a culture deeply connected to nature, resilience, and community.

After regaining full independence in 1905, Norway transformed rapidly, evolving from a modest, rural society into one of the world’s most prosperous and socially progressive nations. The discovery of oil in the late 1960s accelerated this shift, helping Norway build a strong welfare system, a forward-thinking economy, and a reputation for peacebuilding and diplomacy. Today, Norway stands confidently on the global stage, celebrated for its language, outdoor lifestyle, and commitment to equality and sustainability.

We’ve put together a collection of everyday Norwegian words and expressions you won’t usually find in textbooks, designed to help you sound more like a true local. These terms carry cultural nuances, reflect Norwegian humor and values, and offer a deeper understanding of the country’s traditions, history, and way of life.

Start speaking and thinking like a native Norwegian today!

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Norwegian, we recommend that you download the Complete Norwegian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't in any other textbook so you can amaze your Norwegian friends and business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Norwegian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Norwegian today!

AKVAVIT

The word (AKVAVIT, aquavit) refers to a traditional Norwegian spirit distilled from grain or potatoes and flavored primarily with caraway or dill. It holds a central role in Norwegian festive culture, especially during celebrations such as jul (Christmas), påske (Easter), and national events like 17. mai, the Constitution Day. Originating in the 16th century, its name comes from the Latin aqua vitae, meaning “water of life,” a term used throughout Europe for strong spirits believed to have medicinal properties. Over time, it became deeply associated with Norwegian hospitality, cuisine, and tradition.

Production of aquavit is regulated and steeped in craftsmanship. Norwegian distillers follow strict guidelines to preserve authenticity. The base alcohol is distilled from potatoes or grains and then infused with herbs and spices—most commonly caraway, dill, fennel, coriander, and anise. After distillation, the spirit is often aged in oak barrels, sometimes on sea voyages, as in the famous Linje Aquavit, which crosses the equator twice before bottling. This aging process contributes to its golden color and complex aroma.

Aquavit is typically consumed as a snaps (small shot) during meals, served chilled in small glasses. It pairs especially well with traditional dishes such as gravlaks (cured salmon), spekeskinke (cured ham), and sild (herring). In Norway, it is not just a drink but a social ritual. Toasts, or skål, are integral to formal dinners, weddings, and festive gatherings. Proper etiquette requires eye contact while raising the glass, symbolizing trust and fellowship.

Beyond its culinary use, aquavit has historical and symbolic importance. During the 19th and 20th centuries, as Norway developed its national identity, the drink became a marker of cultural distinctiveness, much like bunad (national costume) or friluftsliv (outdoor lifestyle). Its production also reflects Norway’s agricultural heritage, since potatoes became a key crop after their introduction in the 18th century. Distilleries were often family-run enterprises, with recipes and methods passed down through generations.

Today, aquavit remains a protected regional specialty under European Union regulations, recognized as a geografisk betegnelse (geographical indication). Modern producers have expanded the tradition with artisanal versions using locally foraged ingredients such as einebær (juniper berries) or rabarbra (rhubarb). Contemporary Norwegian cuisine often includes aquavit-inspired sauces and desserts, merging innovation with heritage. Exports have also grown, and Norwegian aquavit is now enjoyed worldwide, representing both cultural pride and craftsmanship.

ALLEMANSRETTEN

The concept (ALLEMANNSRETTEN, everyman’s right) is a cornerstone of Norwegian culture and environmental ethics. It grants everyone the legal right to roam freely across open land, forests, mountains, and coastal areas, regardless of ownership, as long as nature is respected. This principle, rooted in ancient customs, was formally codified in the Friluftsloven (Outdoor Recreation Act) of 1957, ensuring public access to nature as a collective good. It reflects the deep Norwegian belief that natural landscapes belong to everyone and should be preserved and enjoyed responsibly.

Under this right, people may hike, camp, pick berries and mushrooms, and swim in lakes or the sea on uncultivated land, known as utmark, without asking permission. However, activities near homes or cultivated fields, referred to as innmark, require consent from landowners. This balance between freedom and responsibility is central to Norwegian social values. Allemannsretten is guided by the unwritten rule ta vare på naturen (take care of nature), emphasizing minimal environmental impact, cleanliness, and respect for wildlife.

The tradition supports Norway’s philosophy of friluftsliv (open-air life), a lifestyle that encourages outdoor activity in all seasons. Families go hiking, skiing, and camping as natural parts of daily life. School programs include outdoor education to teach children the importance of environmental awareness. This connection between people and the landscape fosters mental well-being and strengthens community identity. Many Norwegians describe allemannsretten not as a privilege but as a responsibility to safeguard the environment for future generations.

Historically, the origins of the right to roam can be traced back to medieval laws and rural customs, when boundaries were fluid and land was communally used for grazing and gathering. As Norway industrialized and private property laws developed, these traditions persisted, maintaining access to the wilderness as a vital element of national character.

In contemporary times, allemannsretten has become a model for sustainable tourism and outdoor recreation. It attracts hikers and travelers seeking unspoiled nature while reminding visitors to respect the principle of ikke etterlat spor (leave no trace). The right also plays a role in protecting biodiversity, as it raises awareness about the value of untouched ecosystems. Government agencies and organizations like Den Norske Turistforening (The Norwegian Trekking Association) promote guidelines that combine accessibility with conservation.

BÅL

The word (BÅL, bonfire) refers to an outdoor fire that holds great cultural and social importance in Norway. It symbolizes warmth, community, and connection with nature, playing a central role in outdoor traditions, celebrations, and seasonal rituals. The practice of gathering around a fire is ancient and continues to be deeply rooted in Norwegian identity, especially within the philosophy of friluftsliv (outdoor life), which encourages harmony with nature.

Historically, bål served practical purposes for survival in Norway’s cold climate. It provided heat for cooking, protection from wild animals, and a gathering point for social interaction. Over centuries, it evolved from necessity into a cultural symbol. Lighting a fire in the wilderness or on the coast represents both independence and belonging—a moment to share stories, prepare food, or simply observe the quiet of nature. Norwegian law, under the principles of allemannsretten (everyman’s right), allows people to build small campfires in uncultivated areas as long as safety and environmental rules are respected.

One of the most recognizable traditions involving bål is the St. Hans-aften (Midsummer Eve) celebration, held on June 23. During this event, communities across the country gather to light massive bonfires along fjords and beaches. The flames are believed to ward off evil spirits and celebrate the summer solstice, the longest day of the year. In coastal towns, bonfires can reach remarkable heights, and some regions even hold competitions for the tallest bål. This event unites families, friends, and entire communities in a shared experience of joy and light.

In addition to summer festivities, bål plays an important part in daily outdoor life. Campfires are a traditional feature of hyttetur (cabin trips), hiking expeditions, and skiing adventures. Norwegians use them for grilling pølser (sausages), making pinnebrød (stick bread), or brewing kaffe (coffee) in a kjele (kettle). The fire serves as a symbol of coziness, or koselig (cozy atmosphere), blending comfort and simplicity in natural surroundings.

Environmental awareness also shapes how Norwegians use bål today. The government and organizations like Den Norske Turistforening (The Norwegian Trekking Association) promote responsible fire practices, including bans during dry summer periods to prevent wildfires. Building a campfire has become a mindful act that reflects respect for the land and the traditions tied to it.

BUNAD

The term (BUNAD, national costume) refers to the traditional Norwegian attire worn on special occasions, symbolizing regional heritage, craftsmanship, and national pride. Each bunad is unique to a specific district or town, reflecting local history, colors, and embroidery patterns. Today, it is most prominently seen on 17. mai (Constitution Day), weddings, and confirmations, serving as both festive clothing and a statement of cultural identity deeply connected to Norway’s past.

The origins of bunad trace back to rural folk costumes of the 18th and 19th centuries, when clothing styles varied greatly by region. These garments often indicated social status, marital situation, and local affiliation. In the early 20th century, amid rising nationalism and the desire for cultural renewal, bunad was revived as part of Norway’s search for distinct national symbols following independence from Sweden in 1905. Folklorists and textile experts documented old patterns, fabrics, and jewelry, transforming them into standardized designs still used today.

A bunad typically consists of a wool skirt or trousers, vest, shirt, apron, and shawl for women, while men wear breeches, waistcoats, and jackets. Accessories such as sølje (silver brooches) and beltestakk (belted skirt) hold deep symbolic meaning, often inherited as family heirlooms. Regional versions include the Hardangerbunad from western Norway, known for its red bodice and white embroidery, and the Nordlandsbunad from the north, distinguished by green and blue tones. Every detail, from stitching techniques to jewelry motifs, reflects regional artistry and pride.

Beyond aesthetics, bunad has social and emotional significance. Wearing one demonstrates belonging, respect for tradition, and connection to ancestors. Many families invest in custom-made costumes tailored by skilled artisans, which can take months to complete. The value of a full bunad can be high, but it is viewed as a lifelong possession and symbol of continuity. Even Norwegians living abroad often acquire one as a link to their heritage.

In contemporary society, bunad remains dynamic. Designers and cultural institutions adapt old models to modern needs while preserving authenticity. Some have introduced practical innovations, like lighter fabrics or simplified accessories, to make the costume easier to wear. Debates occasionally arise about cultural appropriation, modernization, and gender norms, showing how strongly bunad resonates in national consciousness.

DUGNAD

The concept (DUGNAD, voluntary community work) embodies one of the most deeply rooted social traditions in Norway, reflecting collective responsibility, solidarity, and cooperation. It refers to unpaid group efforts where neighbors, colleagues, or members of an organization come together to complete a common task, such as cleaning shared spaces, maintaining public areas, or organizing community events. Dugnad has been a defining feature of Norwegian social life for centuries and continues to serve as a key expression of civic engagement and unity.

The origins of dugnad can be traced back to rural Norway, where agricultural communities depended on mutual help to survive harsh conditions. Farmers worked together on tasks such as slått (haymaking), innhøsting (harvest), or repairing naust (boathouses) and stabbur (storehouses). This system of cooperation allowed small communities to share resources and labor in an environment marked by limited manpower and challenging geography. Over time, the tradition evolved from necessity into a social value, symbolizing the Norwegian ideal of fellesskap (community spirit).

In modern Norway, dugnad remains institutionalized across all levels of society. Housing cooperatives, or borettslag, organize spring and autumn cleaning sessions where residents tidy gardens, paint fences, and improve common areas. Schools involve parents in maintaining playgrounds, while sports clubs rely on volunteer work to run tournaments and fundraisers. Participating in dugnad is seen not only as a duty but also as a moral obligation, embodying the belief that everyone should contribute to the collective good.

The cultural significance of dugnad extends far beyond physical work. It strengthens social bonds and promotes inclusion across generations and social backgrounds. Taking part fosters tillit (trust) and reinforces equality, as all participants—regardless of occupation or status—work side by side. It also plays a role in integrating newcomers into local communities, offering immigrants and refugees a natural way to connect with Norwegian culture and language.

In the workplace, dugnad is sometimes used metaphorically to describe joint efforts to achieve goals. Phrases such as nasjonal dugnad (national collective effort) have been employed by authorities during crises, including public health campaigns or environmental initiatives. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the government appealed to the population’s dugnad spirit to encourage cooperation and solidarity in following health measures.

The enduring importance of dugnad reflects broader national values of equality, democracy, and mutual trust. It connects to the Norwegian concept of janteloven (the law of Jante), which discourages individualism and promotes modesty and cooperation. Whether cleaning a shared courtyard, organizing a festival, or responding to national challenges, dugnad continues to symbolize the moral fabric of Norwegian society—a collective effort that sustains both local communities and the nation as a whole.

ISBRE

The term (ISBRE, glacier) refers to a massive, slow-moving body of ice formed by accumulated snowfall compacted over centuries. In Norway, glaciers are among the most striking natural features, sculpting the country’s rugged landscape of fjorder (sea inlets), daler (valleys), and fjell (mountains). They are both scientific treasures and cultural landmarks, symbolizing endurance, purity, and the power of nature. Glaciers play a vital role in Norway’s ecology, tourism, and climate research, forming an integral part of the national identity and environmental awareness.

Norway hosts approximately 1,600 glaciers, covering about one percent of its total land area. The largest is Jostedalsbreen, located in Vestland fylke (Vestland County), spanning over 480 square kilometers and rising more than 2,000 meters above sea level. Other major glaciers include Folgefonna, Svartisen, and Hardangerjøkulen, each with unique geological formations. These ice masses were primarily formed after the last Ice Age and continue to shape the Norwegian terrain through melting, erosion, and sediment transport. Their meltwater contributes to vannkraft (hydropower), one of the country’s primary renewable energy sources.

Glaciers have historically influenced Norwegian life and imagination. In folklore, they were sometimes perceived as living entities—silent giants capable of destruction and rebirth. Legends describe spirits or vetter (nature beings) dwelling beneath the ice, reminding humans of their vulnerability and dependence on natural forces. The vast, ever-changing landscape created by glaciers has also inspired Norwegian art and literature, particularly during the nasjonalromantikk (National Romanticism) movement, when painters and poets celebrated the sublime beauty of the natural world.

Scientifically, isbreer (glaciers) are vital indicators of climate change. Researchers from the Norges geologiske undersøkelse (NGU) (Geological Survey of Norway) and the Norsk Polarinstitutt (Norwegian Polar Institute) closely monitor glacier movement, thickness, and melt rates. Over recent decades, many glaciers have retreated significantly due to rising temperatures, threatening ecosystems and local communities that depend on glacial water sources. This has made isbreer central to environmental education and public discourse about sustainability and global warming.

Tourism also thrives around Norway’s glaciers. Sites such as Nigardsbreen and Briksdalsbreen attract thousands of visitors annually for guided hikes, breturer (glacier walks), and isbresafari (glacier safaris). Safety and conservation are top priorities, with strict regulations ensuring minimal human impact. Local guides provide insights into glacial geology, emphasizing the balance between accessibility and preservation. For Norwegians, exploring glaciers is both a recreational and spiritual experience—a way to witness the majesty of their natural heritage firsthand.

ELG

The word (ELG, moose) refers to one of the most iconic animals in Norway and a powerful symbol of the country’s wilderness and natural heritage. Known as the “king of the forest,” this large herbivore is a common sight in Norwegian woods, wetlands, and mountain valleys. The species, Alces alces, thrives in the northern climate and has been an important part of Norwegian ecology, economy, and folklore for thousands of years.

The elg inhabits forests rich in bjørk (birch), gran (spruce), and furu (pine), feeding mainly on leaves, twigs, bark, and aquatic plants. Its ability to adapt to cold environments makes it widespread throughout the country, from the southern forests of Østlandet to the tundra of Finnmark. The moose population in Norway is estimated at over 120,000 during the summer months, and wildlife management policies regulate hunting to maintain ecological balance. Moose hunting, or elgjakt, is a well-organized tradition that combines sustainable practice with community participation.

For centuries, elg has provided Norwegians with meat, hides, and antlers. Before industrialization, hunting was a vital food source, and moose remains featured prominently in local diets. Today, elgkjøtt (moose meat) is considered a delicacy and is often served as elgstek (roast moose), elggryte (moose stew), or elgpølse (moose sausage). Controlled hunting seasons, established by the Miljødirektoratet (Norwegian Environment Agency), ensure sustainability and animal welfare. Hunters must complete specific training and follow detailed rules on quotas and permitted zones, reflecting Norway’s commitment to responsible resource management.

The animal also holds cultural significance in Norwegian folklore and symbolism. In ancient myths, the elg represented strength, endurance, and independence. Rock carvings, or helleristninger, dating back to the Stone Age, depict moose as sacred beings associated with fertility and hunting rituals. In modern times, the image of the moose appears in art, logos, souvenirs, and road signs, reflecting its continuing presence in the national imagination. The humorous warning sign “Fare for elg” (Beware of moose) has even become a popular tourist symbol.

Encounters with elg are part of daily life in rural regions. Drivers must remain cautious, as collisions with these large animals occur especially during dusk and winter. To prevent accidents, authorities use viltgjerder (wildlife fences) and viltkameraer (wildlife cameras) to monitor movement patterns. Conservation efforts also include maintaining migratory corridors and safe crossing points along major highways.

FJORD

The term (FJORD, sea inlet) refers to the deep, glacially carved valleys filled with seawater that form Norway’s most distinctive geographical feature. These natural formations stretch far inland from the coast, creating dramatic landscapes of steep cliffs, waterfalls, and narrow waterways. Fjords are a defining element of Norway’s national identity, shaping its settlement patterns, economy, and global image. The country’s coastline, among the longest in the world, includes thousands of fjords, each with unique geological, ecological, and cultural significance.

Geologically, fjords were created during the last Ice Age when massive glaciers carved deep U-shaped valleys through rock. As the ice melted, seawater filled these depressions, forming the fjords we see today. The depth of these inlets can reach over 1,300 meters, as in Sognefjorden, Norway’s longest and deepest fjord. Other renowned examples include Geirangerfjorden, Nærøyfjorden, and Hardangerfjorden, which together represent some of the world’s most breathtaking natural scenery. Many fjords are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites, recognized for their geological importance and unspoiled beauty.

The fjord has played a central role in Norway’s history and livelihood. In ancient times, it provided natural harbors for viking (Viking) ships, facilitating exploration, trade, and settlement. Coastal communities grew along these waterways, relying on fishing, farming, and boatbuilding. Even today, many towns—such as Bergen, Ålesund, and Tromsø—owe their existence and prosperity to their fjord locations. The waters are rich in sjømat (seafood), particularly torsk (cod), laks (salmon), and reker (shrimp), sustaining a long-standing maritime economy.

In the modern era, fjords continue to shape Norway’s transportation and tourism sectors. Ferger (ferries) and hurtigbåter (express boats) connect remote villages, while the famous Hurtigruten (Coastal Express) provides daily passenger and cargo service along the western coast. Tourism centered around fjords attracts millions of visitors annually, offering activities such as kajakkpadling (kayaking), cruiseferie (cruise travel), and fjellturer (mountain hikes). This tourism is carefully managed to maintain sustainability and preserve the fragile ecosystems that thrive along fjord shores.

The ecosystem of a fjord is unique. Due to its mix of freshwater from rivers and saltwater from the sea, it supports a diverse range of marine life. Steep cliffs and surrounding forests host species like ørn (eagle) and sel (seal), while cold, nutrient-rich waters encourage plankton growth vital to the food chain. Environmental monitoring programs ensure that industrial activity, including oppdrettsanlegg (fish farms), operates responsibly to prevent pollution and ecological imbalance.

Culturally, the fjord embodies the essence of Norway’s relationship with nature—majestic, practical, and enduring. It has inspired countless works of art, from nasjonalromantikk (National Romanticism) paintings of the 19th century to contemporary photography and film. The expression landet med fjorder (the land of fjords) symbolizes Norway’s global image as a country defined by pristine landscapes and harmony between humans and the environment.

FLÅKLYPA

The term (FLÅKLYPA, Flåklypa universe) refers to one of the most beloved fictional settings in Norwegian popular culture, originating from the stop-motion animated film Flåklypa Grand Prix (The Pinchcliffe Grand Prix), directed by Ivo Caprino and released in 1975. The story is set in the fictional mountain village of Flåklypa, a humorous and heartwarming reflection of Norwegian rural life, ingenuity, and community spirit. It has since become a cornerstone of national identity in film, animation, and children’s literature.

Flåklypa revolves around the eccentric bicycle repairman Reodor Felgen, his friends Solan Gundersen, a cheerful magpie, and Ludvig, a timid hedgehog. Together, they design and build a race car named Il Tempo Gigante, representing the triumph of creativity, teamwork, and persistence. The film combines mechanical innovation, folk humor, and local dialects, capturing both the simplicity and inventiveness characteristic of Norwegian society. Its combination of hand-crafted animation, witty dialogue, and realistic miniature sets created a timeless masterpiece that continues to charm generations.

The production of Flåklypa Grand Prix was groundbreaking in Norwegian cinema. Caprino’s team used detailed puppetry and mechanical animation long before digital technology existed, crafting a cinematic experience that rivaled major international productions. Each scene was built with precision, using miniature landscapes inspired by fjellbygder (mountain villages), småhus (small houses), and verksteder (workshops). The film’s music, composed by Bent Fabricius-Bjerre, incorporated traditional Norwegian folk melodies, reinforcing the cultural authenticity of the story.

Flåklypa reflects several Norwegian values embedded in society. The theme of dugnad (voluntary community work) is evident as the characters collaborate for a common goal. The setting mirrors the koselig (cozy atmosphere) of rural life, where cooperation and kindness triumph over greed and arrogance. It also celebrates norsk oppfinnsomhet (Norwegian inventiveness), portraying a deep respect for craftsmanship and self-reliance. These elements make Flåklypa both entertaining and educational, subtly teaching moral and social lessons through humor and storytelling.

The film’s influence extends beyond cinema. It inspired video games, books, and exhibitions, including the popular Flåklypa Tidene (Flåklypa Times), a fictional newspaper within the universe. The original sets and puppets are preserved at Caprino Studios near Oslo, and the film remains a staple of Norwegian holiday television, often aired during Christmas alongside classics like Tre nøtter til Askepott (Three Nuts for Cinderella). This ritual viewing has become part of the country’s seasonal traditions, reinforcing shared nostalgia and cultural continuity.

GLØGG

The term (GLØGG, mulled wine) refers to a traditional spiced drink enjoyed in Norway during the winter season, particularly around jul (Christmas). It is typically made from red wine or fruit juice heated with spices such as kanel (cinnamon), nellik (clove), ingefær (ginger), and kardemomme (cardamom), often sweetened with sugar and served with rosiner (raisins) and mandler (almonds). Gløgg is much more than a beverage—it is a cultural ritual that reflects Norwegian hospitality, togetherness, and the warmth of indoor life during the dark winter months.

The tradition of gløgg has its origins in medieval Europe, where spiced wine was valued for its flavor and medicinal qualities. It reached Scandinavia in the 16th century and became part of Norwegian holiday customs in the 19th century. Early recipes often included brennevin (spirits) such as akevitt (aquavit) or konjakk (brandy), giving the drink a stronger character suited for cold climates. Over time, non-alcoholic versions made with rød saft (red syrup drink) or solbærsaft (blackcurrant juice) became popular, ensuring that children and non-drinkers could also enjoy it.

Gløgg plays a central role in social gatherings during the Christmas season. It is commonly served at julebord (Christmas parties), juletrefest (Christmas tree festivities), and family visits, often accompanied by pepperkaker (gingerbread cookies) or riskrem (rice cream dessert). Norwegians typically serve gløgg in small cups or glass mugs, allowing the aroma of spices to fill the room. The act of sharing it embodies the spirit of koselig (coziness), an essential part of Norwegian winter culture that emphasizes comfort, candles, and companionship.

Commercial gløgg is available in supermarkets, but many families prepare homemade versions, each with unique ingredients and regional variations. Some add appelsinskall (orange peel), anis (anise), or even a splash of portvin (port wine) for depth of flavor. The process of simmering gløgg slowly over low heat is considered almost ceremonial, as the scent spreads through the home and signals the beginning of the festive season.

In contemporary Norway, gløgg also connects to the broader friluftsliv (open-air life) tradition. It is often brought along in thermoses during skiturer (ski trips) or vinterturer (winter hikes), enjoyed outdoors by the bål (bonfire) or inside hytter (cabins). This dual role—linking indoor coziness with outdoor adventure—illustrates how Norwegians balance warmth and resilience during the coldest part of the year.

GRAVLAKS

The term (GRAVLAKS, cured salmon) refers to a traditional Norwegian dish made by preserving fresh salmon in a mixture of salt, sugar, and dill. The word comes from grave, meaning “to bury,” and laks, meaning “salmon,” a reference to the old method of fermenting fish by burying it in sand or earth near the sea. Modern gravlaks is no longer fermented but cured, offering a delicate balance of sweetness, saltiness, and herb flavor. It stands as one of Norway’s most famous culinary exports and a cornerstone of Nordic gastronomy.

Historically, gravlaks emerged during the Middle Ages as a method of preservation before refrigeration. Fishermen along the coast of Trøndelag, Nordland, and Finnmark regions salted salmon and stored it underground to keep it edible for longer periods. The mild fermentation process gave the fish a distinctive flavor and texture. By the 19th century, as food safety standards improved, the process evolved into the modern cold-curing method that maintains the fish’s freshness while enhancing its taste. Today, gravlaks is prepared by marinating salmon fillets with a mixture of salt, sukker (sugar), and dill, often flavored with akevitt (aquavit) or *pepper.

Gravlaks is typically served thinly sliced with sennepssaus (mustard sauce), flatbrød (crispbread), or lefse (soft flatbread). It is a staple in festive meals such as julebord (Christmas dinners), påskefrokost (Easter breakfast), and formal gatherings. The dish reflects the Norwegian principle of ren smak (pure taste), which values fresh ingredients and minimal processing. It also exemplifies the country’s close connection to the sea, where fishing remains a vital part of the national economy and culture.

In culinary terms, gravlaks occupies a middle ground between raw and cooked food, preserving the natural texture of salmon while intensifying its flavor. It has inspired similar dishes across Scandinavia, including gravad lax in Sweden and gravet laks in Denmark. Norwegian chefs often emphasize the quality of locally sourced fish, especially villaks (wild salmon) and oppdrettslaks (farmed salmon), ensuring sustainable harvesting through strict regulations enforced by Fiskeridirektoratet (Directorate of Fisheries).

GRUNNLOV

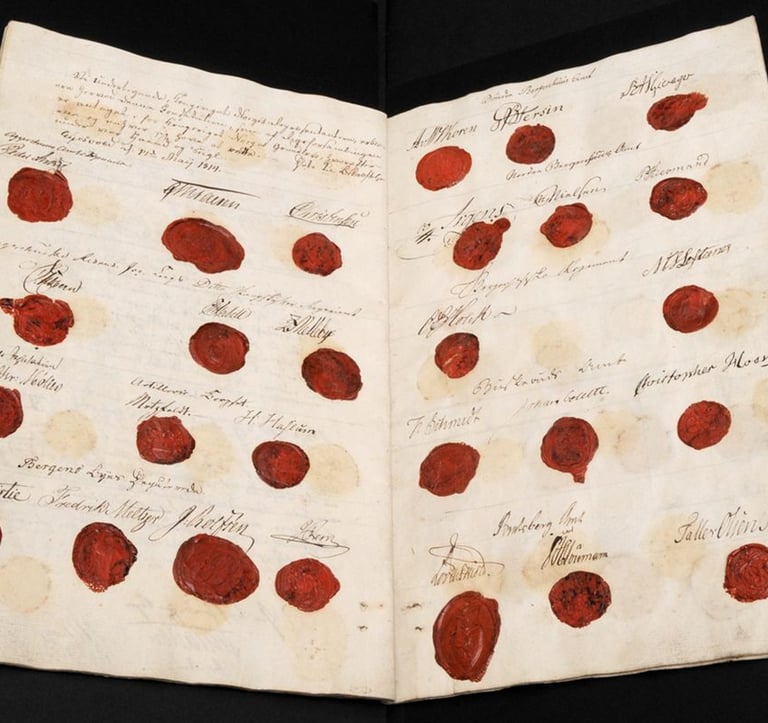

The term (GRUNNLOV, constitution) refers to the foundational legal document of the Kingdom of Norway, adopted on 17. mai 1814 at Eidsvoll by the eidsmenn (representatives). It established Norway as an independent state after centuries under Danish rule and became one of the oldest constitutions in continuous use worldwide. The document embodies Norway’s core democratic values—frihet (freedom), likhet (equality), and rettferdighet (justice)—and has served as the cornerstone of the nation’s political system and collective identity for over two centuries.

The creation of the grunnlov was a direct response to the Kieltraktaten (Treaty of Kiel), which transferred Norway from Danish to Swedish control following the Napoleonic Wars. Determined to secure self-rule, 112 delegates gathered at Eidsvollsbygningen (Eidsvoll Manor House) in April 1814. Over six weeks, they debated and drafted a document influenced by Enlightenment thought and the constitutions of the United States and France. The resulting text declared Norway an independent kingdom with a constitutional monarchy, emphasizing folkesuverenitet (popular sovereignty) and maktfordeling (separation of powers).

The grunnlov consists of three main sections: the form of government, the rights of citizens, and the organization of public institutions. It established the Stortinget (Parliament), Kongen (the King), and domstolene (the courts) as separate powers. Early on, it also contained restrictive clauses regarding religion and citizenship, which were later amended to reflect Norway’s evolving democratic principles. The document was revolutionary for its time, granting broader participation and civic rights compared to most European nations of the early 19th century.

When Norway entered a union with Sweden later in 1814, the grunnlov remained largely intact, allowing Norwegians to preserve legal autonomy and national identity. It was amended again in 1905, following full independence, and later in 1945 after World War II, when democratic institutions were restored. Further changes have addressed gender equality, indigenous samiske rettigheter (Sami rights), environmental protection, and the incorporation of menneskerettigheter (human rights).

The 17th of May, Grunnlovsdagen (Constitution Day), is celebrated nationwide with children’s parades, flags, and speeches honoring the principles of liberty and democracy. Unlike military parades in many countries, Norway’s celebration focuses on civic pride and inclusiveness, reflecting the peaceful, egalitarian spirit of the nation. Schools, local associations, and public officials participate, and cities like Oslo, Bergen, and Trondheim host major events each year.

HARDINGFELE

The word (HARDINGFELE, Hardanger fiddle) refers to a traditional Norwegian string instrument known for its ornate design and distinctive resonant sound. Originating in the Hardanger region of western Norway, the hardingfele resembles a violin but features four main strings and four or five sympathetic strings beneath them that vibrate in harmony. It occupies a central place in Norwegian folk music, particularly in bygdedans (village dance) traditions, and remains one of the country’s most important symbols of cultural heritage and craftsmanship.

The origins of the hardingfele date back to the mid-17th century. The earliest surviving examples were made by craftsmen in Hardanger and Telemark, regions renowned for their woodworking and musical traditions. Unlike the standard fiolin (violin), the hardingfele is richly decorated with rosemaling (floral painting), perlemorinnlegg (mother-of-pearl inlay), and intricately carved løvehode (lion’s head) scrolls. Its sympathetic strings, or understrenger, give the instrument its unique shimmering tone, creating a natural reverberation that fills halls and open-air settings alike.

Musically, the hardingfele is used to perform slåtter (folk tunes), which are often dance melodies passed down orally for generations. These tunes accompany traditional dances such as springar, gangar, and halling, each with regional rhythmic variations. The hardingfele player, or spelemann, occupies a respected role in local culture, serving both as an entertainer and a guardian of musical tradition. Tunes are rarely written down; instead, they are transmitted by ear, ensuring the preservation of local styles and nuances.

In the 19th century, as Norway’s national identity developed, the hardingfele became a symbol of independence and rural pride. It appeared in literature and visual arts associated with nasjonalromantikk (National Romanticism), a movement celebrating Norwegian landscapes, folklore, and peasant life. Composers such as Edvard Grieg drew inspiration from hardingfele music, incorporating its rhythms and tonalities into classical compositions like the Peer Gynt Suite. This fusion helped elevate folk culture into the national mainstream.

Today, the hardingfele remains a living tradition. It is taught in folkehøgskoler (folk high schools), kulturskoler (community music schools), and through national organizations such as Landslaget for Spelemenn (National Association for Fiddlers). Each region maintains its own stemmesystem (tuning system), resulting in diverse soundscapes across the country. Contemporary musicians blend the hardingfele with jazz, rock, and electronic genres, expanding its reach while preserving authenticity.

The craftsmanship behind the instrument is itself an art form. Skilled fiolinmakere (violin makers) use locally sourced woods such as maple and spruce, continuing techniques developed centuries ago. Each instrument requires meticulous construction to achieve the balance between visual beauty and acoustic resonance. Exhibits in museums like Norsk Folkemuseum (Norwegian Museum of Cultural History) and Hardanger Folkemuseum showcase historic and modern examples, underlining its enduring relevance.

HYTTE

The term (HYTTE, cabin) refers to a small house or cottage, typically located in rural, mountainous, or coastal areas, used for recreation and relaxation. The hytte occupies a central role in Norwegian culture, symbolizing simplicity, closeness to nature, and a slower rhythm of life. More than a physical structure, it represents a lifestyle that balances work, family, and friluftsliv (open-air life), emphasizing time spent outdoors and freedom from everyday stress.

There are more than half a million hytter across Norway, reflecting their importance to national identity. Traditionally, hytter were modest wooden buildings without electricity or running water, used by farmers and fishermen as seasonal dwellings during seterdrift (summer pasturing) or coastal work. Over time, they evolved into leisure retreats, often passed down through generations. Many families still own familiehytte (family cabins), gathering there on weekends and holidays for hiking, skiing, fishing, or simply enjoying ro og stillhet (peace and quiet).

The design of a hytte varies depending on its location. In mountain regions, fjellhytte (mountain cabins) feature turf roofs and fireplaces for warmth, while along the coast, sjøhytte (seaside cabins) are built close to the water for easy access to båt (boat) and fiske (fishing). Interior decoration is typically simple, focusing on wood, wool, and muted colors that blend with the natural environment. Many include peis (fireplace), the focal point of koselig (cozy) evenings after long days outdoors.

The cultural significance of the hytte extends far beyond leisure. It serves as a sanctuary where Norwegians reconnect with their roots and environment. The expression å dra på hytta (to go to the cabin) is synonymous with escaping urban life, turning off digital distractions, and enjoying self-sufficiency. Activities such as chopping wood, fetching water, and cooking on a gas stove are viewed not as inconveniences but as satisfying rituals that reinforce independence and humility.

During påskeferie (Easter holiday), tens of thousands of Norwegians travel to their mountain cabins for skiing, sunbathing on snow-covered terraces, and reading crime novels known as påskekrim (Easter crime fiction). Similarly, vinterferie (winter vacation) and høstferie (autumn break) see families spending quality time together at their hytter. For many, these traditions represent the rhythm of Norwegian life—alternating between the efficiency of city routines and the restorative simplicity of nature.

Economically, hytter contribute to local tourism and rural development. Construction and maintenance support small businesses, while rentals provide income for local communities. The Den Norske Turistforening (DNT) (Norwegian Trekking Association) maintains an extensive network of public turisthytter (tourist cabins), allowing travelers to explore remote regions on foot or ski. These cabins, often unstaffed and self-service, operate on trust, illustrating Norway’s strong culture of tillit (mutual trust).

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Norwegian, we recommend that you download the Complete Norwegian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't in any other textbook so you can amaze your Norwegian friends and business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Norwegian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Norwegian today!